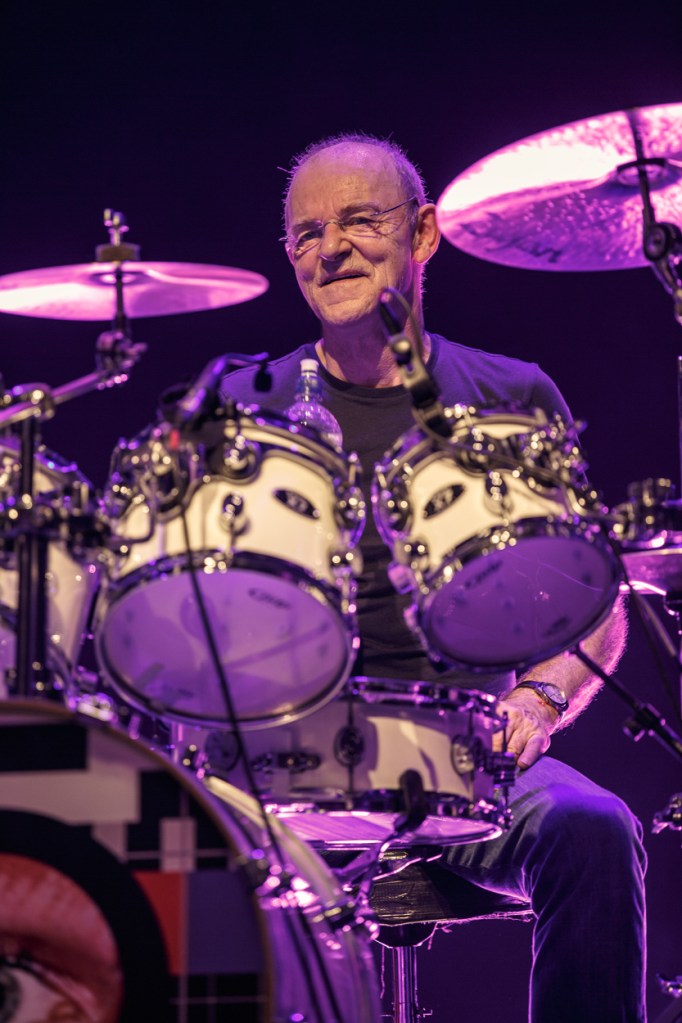

You’d be hard pressed to find a ‘greatest albums of all time’ list that doesn’t feature The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. Between the stellar musicianship, high-concept writing, glam imaging and raunchy coolness, Ziggy Stardust is an album that defies age, an untouchable standard for the flashier side of rock. For the uninitiated, the album centres on David Bowie as Ziggy Stardust, backed by the extraterrestrial Spiders from Mars, an alien come to save the world only to fall victim to rock-and-roll excess. The opening track, ‘Five Years’, is a dramatic catalogue of reactions to impending, world-ending doom. Rising from the silence, Woody Woodmansey’s drum beat pulses the song, and the album, into its apocalyptic groove.

If you hear any kind of percussion being played on The Man Who Sold the World, Hunky Dory, Ziggy Stardust or Aladdin Sane, it will have been hit by Woodmansey. Moving from Driffield to London in March 1970, the drummer joined up with Bowie, Tony Visconti and Mick Ronson to fulfil his dream of becoming a rockstar. Fifty years on, he has reunited with Visconti, touring the country as part of the supergroup Holy Holy to perform some of Bowie’s best songs once again.

According to Woodmansey, his involvement with Holy Holy was something of a happy accident:

‘It wasn’t my idea to put Holy Holy together. I kind of got into that by accident, really. I’d just played two songs at a festival with this band that had been put together. There was two out of Spandau Ballet, Bob Geldof’s guitarist, and Clem Burke from Blondie on drums. And they said, well, come and do a guest show. So, I did.

‘And it was amazing in front of a young audience, a big audience. But I didn’t realise I’d be stood at the side watching Clem Burke play all my parts! I’d be going, oh no, not that one. I just wanted to walk up and just take them off him. F*cking boring, get off,’ he cackled, before adding, ‘But he’s a really cool guy. It’s sad we lost him.’

When he did eventually get behind the drum kit, he said that he realised what he was in for: ‘I realised, hell, I was 20 when I played this. And it was a struggle, some of them. How the hell did I do that? And I had to get match fit again to be able to do it. To actually pull it off with the same intention and everything, you know.

‘But it’s been good. And my style’s changed slightly. Funnily enough, we’ve been touring since the last ten years, basically. And I can’t honestly say I listened to any of the albums to relearn. I just knew it all. But I also realised how much I’d changed some parts that were not for the better. You know, just naturally, ‘oh, I feel like doing that’, but it really didn’t improve on the original.’

Although he stopped working with Bowie in the mid ‘70s, Woodmansey said that he can feel his own influence throughout the setlist, while growing to better appreciate tracks from later in Bowie’s discography:

‘It’s been interesting because there was some probably in the 80s that sounded like me. It wasn’t me, but it sounded like me. And it made me think that I played it! The drum beat on ‘Rebel Rebel’ is what I would have played.

‘I did ‘Ashes to Ashes’, which I like as a song, right? Never played it, so we put that one into the set for this tour. And I initially thought it’s really simple, but playing it is amazing. You’re basically playing just two different beats that keep alternating. But the feel of it is amazing, and you wouldn’t get that just listening to it, if that makes sense, you know?

‘We have this policy of either I played on it, or Tony [Visconti] and I played on it, or Tony produced it. We don’t want to just pick anything that we had nothing to do with, so we’ve done some from Blackstar as well. And they’ve been, again, really emotional to play.

‘I guess, because his passing was connected with Blackstar, doing tracks from that are really like, whoa. Heavy, but I don’t know, a good heavy.

‘You know that Johnny Cash one, ‘Hurt’. Yeah, brilliant song. You hear that, and some people go, oh my God, how can you listen to that? That’s so disturbing. But it’s beautiful.

‘So, it’s got elements of that, some of that later Bowie stuff that I really like. I mean, that’s where [the Spiders] got on, when he kind of introduced us to Lou Reed and Iggy Pop. More Lou Reed. It was decadent. It was dark. But it had a good vibe about it, you know? And we liked that.’

For a bit of local flavour, Woodmansey mentioned York in his autobiography, Spider From Mars: My Life With David Bowie. Recounting his earliest memories of when he was in proto-glam band The Mutations, Woodmansey called York’s Enterprise ‘one of our favourite places’, or as he later described, ‘a dank cellar that played cool music like Tamla and early soul.’ Although it has swapped disco music for a variety of different hobbyist clubs, the Enterprise is still run by Neal Guppy, who I had a great chat with about the different iterations of his business. On hearing the Enterprise’s good health, Woodmansey was thrilled:

‘That’s fantastic to hear that. That’s really cool. We played at The Enterprise Club quite a lot in my second band that I was ever in, and it was mods, basically mods. But underground mods.

‘It was an amazing atmosphere just to play in that, you know. He had this listening room where you’d listen to albums or comedy albums, and we’d just go and listen to Monty Python albums, The Goons, just all old stuff. It became part of the band’s culture. Do you know what I mean?

‘And it turns out Bowie had done the same. Before I knew him, he’d listened to all that stuff. Mick had done the same before I met Mick. So, that was a reality that we had. You know, in the middle of a recording session, somebody would just say, “Have you been shopping?” You know, like, “what did you buy? A piston engine?” You’d just go into this monologue. And it was amazing because everybody knew it. It was cool.’

Woodmansey’s influence obviously stretches far beyond York. As casually as he can quote Monty Python, he can throw a curveball like ‘I did a few years with Art Garfunkel’:

‘I had a friend, Nicky Hopkins, the keyboard player, was staying with me for about a year. And he got the job of putting a band together for Art for this European tour. And he said, do you want the job? And I was like, whoa.

‘I thought, it’s worth the challenge. And it was a challenge, because one of the top session players, Steve Gadd, had done most of the drums on his albums.

‘There’s a certain, without going into drum speak, there’s a certain laid-back approach to Gadd’s playing. And I think a lot of that comes out of L.A., whether it’s just the “I don’t give a shit” attitude or whatever. “I don’t care whether I finish this drummer or not”. I found that really hard, but it gave a certain, oh, looseness to it. Yeah. And I found that really hard. I could only play it like that by imagining I was drunk.

‘Playing with Art was amazing. The voice. It was the voice, when you’re in front of 42,000 people like we did in Antwerp. It was at the end of college, and we just did ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’. We had a 100-piece orchestra on stage with us. It was just outstanding. It was so good that I forgot to play it. I was listening. I became the audience. Nicky Hopkins was glaring at me. And I just managed to come in on time.

‘I found his voice amazing to play with, you know. And I did some work with Joe Elliott and Phil Collen from Def Leppard, doing Bowie stuff, funnily enough. And that, again, was doing Bowie stuff from a different angle. It was still as good and as valid as what Bowie did, but with Joe singing it and Phil playing what Mick played, it had a different thing but equal.’

Woodmansey wasn’t as complimentary for modern music. Apart from Rival Sons and Foo Fighters, he said that for most songs ‘nowadays, you sit and listen and you don’t know if there’s anyone on it. It’s just shallow. It’s an instant coffee. Rather than get your percolator out and make a decent coffee, it’s an instant one. But you’re not walking about going, oh, I can’t wait for another instant coffee.’

Inevitably, the conversation steered back to Bowie. Woodmansey said that his own input struck him most ‘when you’re in the middle of a movie like The Martian or something like that. Or what’s that, The Avengers of the Universe?’ I think he meant Guardians of the Galaxy, where ‘Moonage Daydream’ comes in as a giant robot head floats through space.

He continued, ‘I’m totally engrossed in the movie. I’m really in it, and I’m enjoying it. And then all of a sudden [‘Starman’ in The Martian’] starts, “ding, ding, ding, ding“. And I go, whoa, whoa, whoa, for real. You know what I mean? That’s me coming back at me. Yeah, so that’s weird.

‘I mean, it’s always one of those wicked things, really, where any good music just seems to float down the time stream.’

Unsurprisingly, Woodmansey doesn’t regret moving to London and meeting Bowie, despite having a deputy foreman position waiting for him at Driffield’s Vortex factory. He laughed before adding, ‘It was just another way of making a spectacle of myself, you know what I mean? It must have been 50 years ago, maybe, and I’d still kept in touch with a couple of people.

‘It got shut down. It’d been good for a long time, you know. And they had a staff weekend in London, and they’re from Yorkshire so they probably don’t get to London that often, you know, so it was a big deal. And they invited me to go, so I went.

‘I hadn’t seen them for years, you know. And they just said, “oh, you made the right decision, you know.” Not because of what I did, playing with Bowie, but because the factory shut down. They were essentially saying, “You’ve still got a job, but we don’t.” I thought that was really funny.”

Thankfully, he didn’t spend his life in a glasses factory. Instead, he laid the foundation for some of Bowie’s greatest albums.

‘I think that it did kick the music business up its backside. It put it back on track, gave it back its purpose. It’s supposed to have controversy in it. It’s supposed to be rebellious. It’s supposed to be edgy. And it’s supposed to be not liked by the past generations.

‘It’s supposed to start new things off. And it’s supposed to be bright and exciting, you know. I think we managed to do it in our way. Bowie took us on a cultural journey. Saying, like, “you’re not just a rock and roll drummer. It’s not just a rock and roll band. You’re involved in light and presentation and fashion.” Being able to apply Bowie’s ideas and making it our own and doing it as a band, we pulled it off, you know.’

Although, if there was one thing that Bowie and his music would be remembered for in a century’s time, Woodmansey said, it would have to be that he ‘had the best-looking drummer in the business’.

Pop your email below and never miss an article again!

Leave a comment